Eyrie Wines - Dundee, Oregon

EYRIE VINEYARDS: THE PLACE

Wouldn’t you have liked to be there the day Jason Lett did these watercolors of the Eyrie vineyards?

Look at them. They are painstaking yet fluid. Individual vinerows, remarkable trees, and orientations of the horizon all glide or stipple across the image. Mount Hood’s position in one tells us that the vineyard is positioned due south. The paintings are filled with information, but they also carry the jovial sense of a life lived among these vines. The seeping watery colors drip with Oregon history, and a winemaker sketching out his family’s history the way he wants it to live on into the future. Consider that photographs or maps would have done the purpose to show these vineyards as place — but Jason and Eyrie are more impressionistic. The sight from Jason’s eyes tells us more than any photograph.

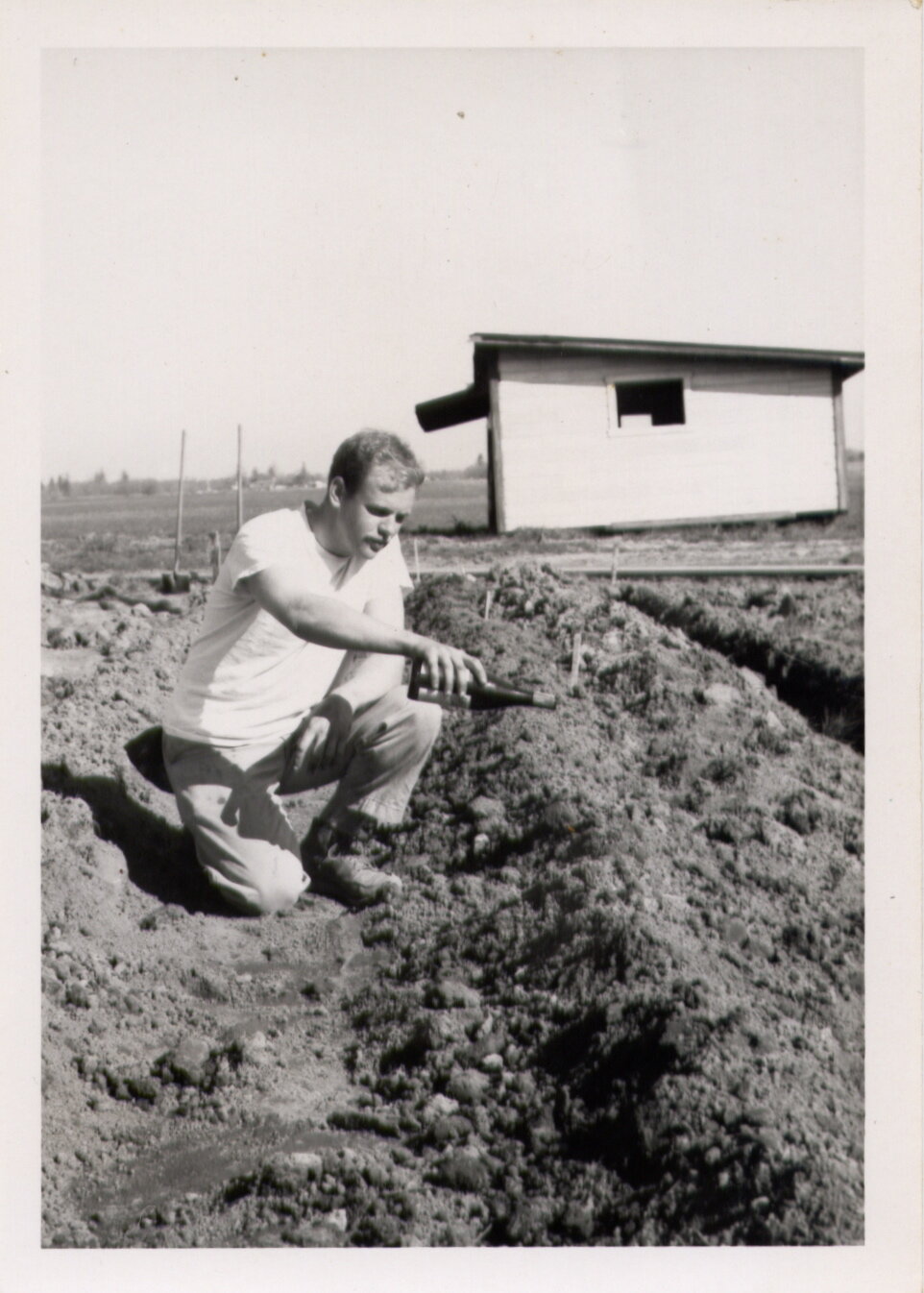

Jason is part of the first crop of second-generation winemakers in Oregon. His father, David Lett, planted the first pinot noir vines in the Willamette Valley in 1965. David did so with a mixture of experience and greenness. He was a highly educated UC Davis graduate, and came to Oregon with a scholastic inkling about the grape’s ability to thrive in this region’s climate but no context from which to draw. So how did David decide where to plant grapes? He drove around with a shovel in the back of his truck and dug holes, filling them with water and comparing the drainage of the soil. He found a spot in the Dundee hills, where the marine sediment is worn down to expose the water-holding decomposed basalt Jory soils. He dug a hole that drained to his liking and signed a few papers. He was ready with his shovel and planted 3000 vines of pinot noir, pinot gris, pinot meunier, chardonnay, and chasselas doré, and started the wine industry as we know it today in Oregon. Jason keeps his father’s hole-digging bore on proud display in the winery today in McMinnville, a trident of discovery and delving.

We are watching Jason paint out the Eyrie Vineyards’s future, with only the smallest dab of context. We often write about and feature European winemakers who come from the fifth, sixth, uncountable generations of people working on the same ground as they do. We are now seeing that first shift play out in our backyard, in this nascent, still wild wine region. Jason grew up around the winery, left for a number of years studying botany and working in Montrachet, and finally came back to work at the winery starting in 2004 with a healthy dose of scientific skepticism.

Jason is getting even closer to the ground. With 53 years of organic Oregon farming under his belt, Jason has deep intimacies with the land. Like his father, he is a radical in his unparalleled attention to the landscape. On the edge of Outcrop vineyard are a few cherry trees. Jason tells us about making a cherry pie from the fruit, so tart and vibrant that it was like “a slap in the face from Demeter herself.” In the cellar, too, the place starts to take shape by the relationship of these different kinds of plant life: the block of pinot noir closest to these trees ferment with a strain of yeast that Jason believes comes from the fallen cherries on the ground. Jason likes to quote his father many years ago saying that it is a “moral imperative” to make wine that expresses the site. Today he might say that making expressive wine is only part of the moral imperative of honoring a place.

What exactly is this ground that Eyrie grows on? To find the answer, take a walk from Outcrop vineyard to the Eyrie vineyard on a shining July morning. There is a particular forest- and blackberry-edged swale of ground between the two that whispers of wisdom. It dips down between two hills connecting the two vineyards and likely marks one border of the rock outcrop for which the vineyard is named (it’s planted atop a volcanic tier that split off from surrounding formations).

click to enlarge

As we walk from Outcrop to Eyrie, Jason asks, do you realize we just crossed over six different soil types? Nekia is the shallowest, a type of Jory, and Woodburn the deepest, an ancient marine deposit. Before we walk into the old vines, we must coat the soles of our boots with bleach to kill any outside bacteria. Since the year 2000, those precious own-rooted old vines planted by David have caught phylloxera, the louse that almost destroyed Europe’s wine industry. There’s no telling where the phylloxera came from, The disease slowly strangles the life out of the roots, drastically reducing the yields of the vines until they decrescendo into death. Just as the vines passed the half-century threshold, and just as they land in capable, informed hands, could they vanish?

Eyrie isn’t going to give up that easy. They are experimenting with a kind of grafting more typically used with citrus and other fruit trees called inarch grafting, where a new vine is cultivated alongside the sick one and eventually folded inside of it. Since the phylloxera attack the rootstocks of vitis vinifera, they’ll cleverly substitute the root stock for a resistant one. Theoretically, Jason’s great-great grandchildren will be more able to see how this one plays out. Jason seems undaunted and curious about these long-term projects. In the short term, Jason is planting, growing, and making wines from a variety new to Oregon called Trousseau, a variety that originates in the Jura. As Russ points out, these are also the original vines of Trousseau in Oregon. When new pinot is planted (as it has been at their Roland Green vineyard), new vines of pinot noir are planted on disease and drought-resistant rootstock. Everywhere we see Eyrie continuing to take important strides for a changing future. In 300 years, will the Willamette Valley be known for Trousseau?

And then we walk back from Eyrie to Outcrop. We talk about farming. Jason repeats something his father often told him, that plants have been on the earth for 500 million years. Humans? 50,000 years (editior’s note: we can’t vouch for the accuracies of these numbers — take it up with Jason Lett!). He goes on to say that in his opinion farming movements with names and staunch practices put a person in the center of everything, commanding the vines. Humans mistake themselves as the only rational link in the system. Yet the plants know how to take care of themselves, even when in the artifice of agriculture.

Rounding that corner was like following his brush with my eyes. We walked the same path there and back but neither of us saw the same thing twice. Where David started by wielding a prod into the ground, Jason now gestures with a brush.

When in stock, wines from this producer appear below. Click on each wine for more detail.